Wilton presentation demonstrates historical significance of postcards

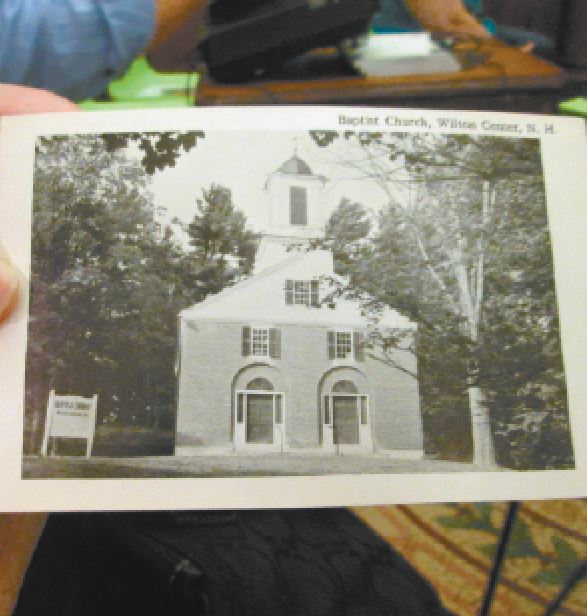

Photos by JESSIE SALISBURY This postcard shows the former Wilton Center Baptist Church.

WILTON – Postcards were the email of the 19th century, sending short messages of all kinds, Robert Perreault told an enthusiastic audience at the Wilton Public & Gregg Free Library on Wednesday, May 17.

“With same-day mail delivery, or twice a day in cities like Manchester, and before telephones, postcards were the way to send messages,” he said.

Perreault is the author of several books on postcards, a lecturer, a teacher of French at Saint Anselm College and a postcard collector, -or, he said, “a deltiologist.”

Perreault has about 13,000 cards that feature Manchester. He presented a variety of them as a slideshow.

He said he began collecting in about 1974, “when cards were affordable, 5 or 10 cents each at flea markets and antique stores.”

After the Bicentennail in 1976, “People began taking more interest in local history,” Perreault said. A rare card now can cost more than $100.

Postcards were introduced in the late 18th century, he said.

“Letters could be written on one side,” he said.

After photography was introduced, pictures were black and white, but were hand-colored in Germany until 1914. World War I forced American photographers to take up coloring.

Most card pictures were taken by local photographers and frequently published locally.

Postcards are a record of local history, Perreault said, showing the changes in buildings and streets.

Before 1907, he said, “You could only write on the image side of the card, in the margins of the picture. After that, the address side was divided in half with space for the message.

Most cards were written by women, he said.

Many people collect particular scenes, such as railroad stations or fire trucks. Family cards can provide a history. He had several from one family, including a response.

Postcards, both the pictures and the messages, “cover important issues, customs and habits, changes in language, and can connect you to the people who once lived in your house,” he said.

Perreault read a selection of postcard messages that noted people’s health or travel, or were intriguing comments that raised a lot of questions but offered no clue as to the people involved or the events they mentioned.

His views of Manchester included the Amoskeag Mills, both inside and out; elaborate buildings that no longer exist; before and after views of Elm Street and Hanover Street; City Hall, former bridges and West Manchester, the “Flat Iron District.”

Although people were invited to bring their own postcards to share, only Laurie Bourgoine did. She lives in the former Wilton Center Baptist Church, and had views of the church from the early 1900s.

The program was presented through the New Hampshire Humanities Council.